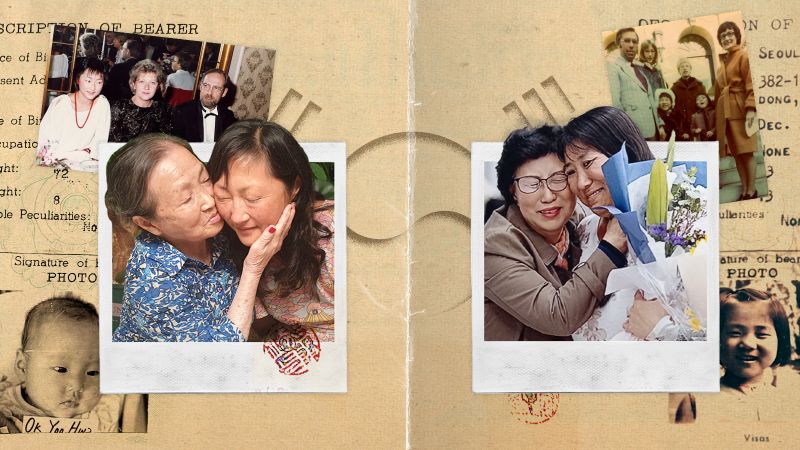

Marianne Ok Nielsen never wanted children, or a family of her own. She used to tell friends she didn’t feel worthy of that kind of life.

For most of her 52 years, she believed she’d been abandoned by her parents as a baby; found on the street in 1973 by police in Daejeon, South Korea, a city about 90 miles south of the capital Seoul.

“I was discarded like garbage. Nobody wanted me… That’s what I was,” said Nielsen, who grew up in Denmark, the home of her adoptive parents. “When your mom doesn’t even want you, who would want you? Can you then be loved by anyone?”

Her Danish mother, who passed away last year, once told Nielsen that her birth mother had probably “given her up out of love” because she couldn’t afford to raise her.

It was a story likely told to console a child, but one that provided cover to a lucrative business built on the “mass exportation” of babies – some with fake names and birth dates – to foreign parents in at least 11 countries, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported this year, in the first official recognition of the scale of the injustice.

Continue reading the complete article on the original source