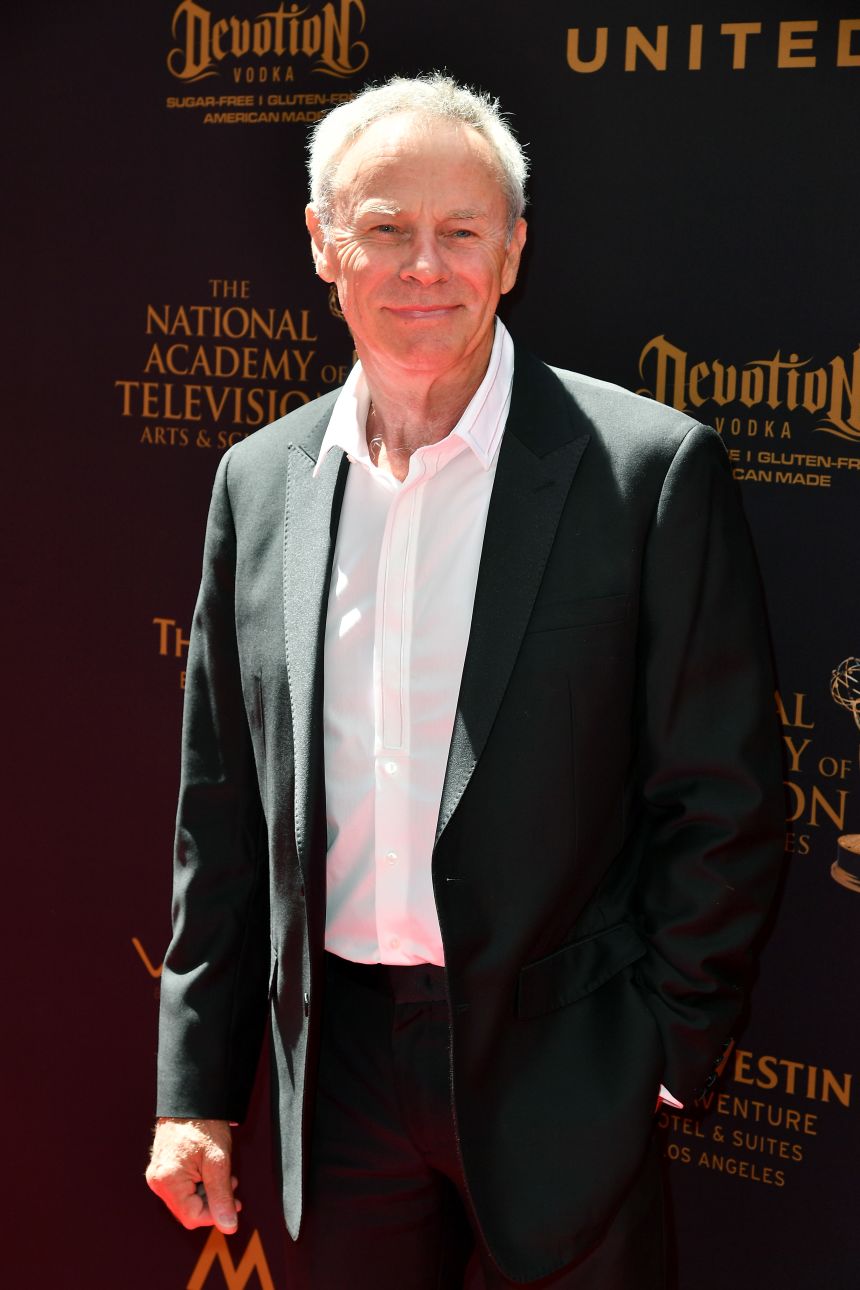

Kamchatka governmentVladimir Akeev, from the remote village of Sedanka in Russia's Far East, died four months after signing up to fight in the Ukraine warIn the fishing village of Sedanka, in Russia's Far East, life is hard.Most homes lack basic amenities such as running water, indoor toilets and central heating, despite temperatures routinely falling to -10C (14F) during the winter months.Ringed by forest-tundra and bogs, its district centre can only be reached from May to October by river boat or vehicles with tracks, and in winter only by snowmobile or helicopter.There are few local jobs and most villagers survive by fishing and growing their own food.And now almost all of Sedanka's men aged 18 to 55 have gone, according to locals, having joined Russia's war in Ukraine."It's heartbreaking – so many of our people have been killed," says Natalia, a villager whose name we've changed for her security, in an interview with the BBC World Service."My sister's husband and my cousins are at the front. In almost every family, someone is fighting."Located on the north-west edge of the Kamchatka Peninsula, near the Sea of Okhotsk, Sedanka is more than 4,300 miles (7,000km) from Ukraine's front lines.The American city of Anchorage, across the ocean, is roughly half that distance.Thirty-nine men from the village signed contracts with Russia to fight in the war from a total population of 258. Of these, 12 have been killed and another seven are missing."All our men have left for the special military operation," a group of women told the regional governor when he visited in March 2024, using the Kremlin's language for its war in Ukraine."There is no-one to chop firewood for winter to heat our stoves," they added in an exchange shown on state TV.The BBC, along with Russian news outlet Medizona and volunteer researchers, has so far verified that 40,201 Russian soldiers were killed in 2025.According to our analysis, we estimate that the total number killed in 2025 will reach 80,000, which would be the most deadly year for Russian losses in Ukraine since the full-scale invasion was launched on 24 February 2022.This calculation takes into account obituaries that cite 2025 as the year of death or burial, but we have not yet fully processed or cross-checked.Confirmed deaths for 2024 now stand at 69,362 – roughly comparable to the combined totals for 2022 and 2023 – and the curve has steepened since late 2024.We have confirmed the deaths using official reports and a probate data registry – an official registry of cases after someone dies – as well as newspaper articles, social media posts from relatives or close friends and data from new memorials and graves.In total, the BBC has now identified the names of 186,102 Russian soldiers killed in the war.The true death toll is generally accepted to be much higher, as many deaths on the battlefield are not recorded.Military experts believe our analysis might represent 45-65% of the total, putting the potential number of Russian deaths at between 286,000 and 413,500.Ukraine has also sustained heavy losses.Last month, President Volodymyr Zelensky told French broadcaster France 2 that "officially" 55,000 Ukrainians had been killed on the battlefield.In addition, a "large number of people" are considered officially missing, he said, though he did not give an exact figure.Based on estimates from sources including the UA Losses website, which the BBC has cross-referenced, we estimate that the number of Ukrainians killed is as high as 200,000.Kamchatka governmentVladimir Akeev died in the war, four months after signing an army contractMost Russians killed in the war have Slavic surnames.But losses are disproportionately high among small indigenous groups, especially in economically depressed areas of Siberia and the Far East, such as Sedanka.Sedanka is home mainly to Koryaks and Itelmens – indigenous groups who, under wartime rules, can be exempted from mobilisation.Anti-war activist Maria Vyushkova says Russian state TV amplifies stereotypes about indigenous communities being "born warriors" and skilled shooters in order to encourage them to join the war."Many indigenous communities take pride in that heritage as part of their identity. The Kremlin uses this pride to recruit for war," Vyushkova says.One of the men from Sedanka who joined the conflict was Vladimir Akeev, 45, a hunter and fisherman, who signed a contract with the army in the summer of 2024.Four months later he was killed in combat.Mourners at his funeral in November 2024 were only able to reach the cemetery by snowmobile, and Akeev's coffin arrived on wide wooden sleds.Elsewhere, confirmed losses from indigenous groups include 201 Nenets, 96 Chukchi, 77 Khanty, 30 Koryaks and seven Inuit.As a proportion of males between the ages of 18 and 60, this equates to an estimated 2% of Chukchi, 1.4% of Russian Inuit, 1.32% of Koryaks and 0.8% of Khanty.The BBC's analysis shows that 67% of the dead are from rural areas and small towns – classed as those with populations under 100,000 people – even though 48% of Russia's population lives there.The rate of losses was smallest in major cities, with Moscow having the least deaths per capita – five people for every 10,000 males, or 0.05%.In poorer regions, such as Buryatia in eastern Siberia, and Tuva in southern Siberia, the death rate is 27 to 33 times higher respectively than in the capital.The main driver of this gap between cities and rural areas is the difference in economic development, pay and education, says demographer Alexey Raksha.As a result, soldiers from poorer regions and ethnic minorities make up a larger share of the army and of the dead than the overall population, he says.Regions with a high share of losses had lower life expectancy even before their men joined the war, another Russian demographer told the BBC."For many, the driver is not only poverty but a lack of prospects – the feeling that there is nothing to lose," he says.Kamchatka governmentOne in five houses in Sedanka, built during Soviet times, has been deemed by the state to be unsafeIn Sedanka, a monument to "participants of the special military operation" was unveiled in autumn 2024.Last year, the regional government pledged to bestow the honorary title of "village of military valour" for the participation of its men in the war.It also promised a support programme for families of Sedanka's soldiers.Yet the village has still not received its honorary title nor has much of the promised support for soldiers' families arrived.Roofs on the homes of four contract soldiers were fixed after falling into disrepair, but only after significant media attention.One in five houses, built during Soviet times, has been deemed by the state to be unsafe.Its sole school has been classed by officials as being in a state of emergency, with some walls at risk of collapse.All of this has been compounded by the loss of the village's working-age men to Russia's war in Ukraine.Additional reporting by Yaroslava Kiryukhina and Natalia Maca Groca.War in UkraineRussiaUkraine

Continue reading the complete article on the original source